Dearest monks, artists, and pilgrims,

We wish you radiant blessings of Easter and the joy of new life out of death!

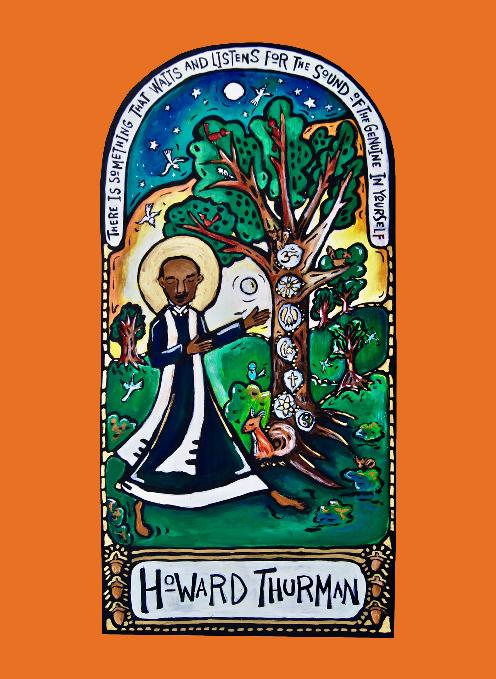

Next Saturday, Lerita Coleman Brown will be leading a retreat for us on the wisdom of Howard Thurman and the healing power of mystical love.

Here is a brief excerpt from her wonderful book What Makes You Come Alive where she explores Thurman’s wisdom about anchoring ourselves in a radical trust in God’s love:

***

One night in 1910, Howard Thurman’s mother woke him up and coaxed him outside. She wanted him to catch a glimpse of Halley’s Comet, which is only visible from earth about every seventy-five years. Thurman’s father had died a few years earlier. Looking up at the comet blazing against the Florida sky that night, young Howard asked his mother what would happen if the comet fell to earth. She looked at Howard with great serenity. He need not worry, his mother told him, because God would take care of them.

This experience stayed with Thurman his entire life. “It was not until my experience with Halley’s Comet that there began to emerge a faint but growing sense of personal destiny, religious in tone and spiritual in accent,” he writes in his autobiography. Ever since, he claims, “I have never been totally cut off from a sense of the guidance of my life. . . It was more than mere ego-affirmation, as important as it is—it was a clue to my self-worth in the profoundest sense. It was the shield against the denigration of my environment; but much, much more.”

Howard Thurman narrates this same event in Jesus and the Disinherited: “The majestic power of my mother’s glowing words has come back again and again, beating out its rhythmic chant in my own spirit,” he writes. “Here are the faith and the awareness that overcome fear and transform it into the power to strive, to achieve, and not to yield.” Without intending to describe a psychological phenomenon, Howard Thurman points to the way that anchoring ourselves in God leads to high levels of self-esteem and self-efficacy. As he notes, a formidable faith and assurance springs from the conviction that “I am a holy child of God.” It exudes a reliance on God’s guidance and protection. Marcus Borg would later describe this same stance espoused by Jesus as more than a mere belief in God but, rather, as a radical trust in God.

As I closed my heavily underlined copy of Thurman’s autobiography, I kept thinking of that moment between a young Howard and his mother, the way she used a child’s question to strengthen his sense of being God’s beloved child. That scene illumines so much. Howard Thurman wanted people to see themselves as creations of God and to convey that same awareness to children. This certainty—that he was a holy child of God—anchored and guided Thurman. He understood that knowing, believing, internalizing, and acting from a divine center transforms all of life. How could he spark this wisdom in other denigrated human spirits: Black people in America who yearned to know and express their authentic selves?

Thurman garnered immense personal strength from defining himself based on his spirit, his inner self, rather than by attributes projected onto him by society. Understanding what it meant to be a holy child of God—to possess a spiritual self—he discovered its link to self-esteem, achievement, and self-actualization. In one recorded conversation, Thurman describes it this way: “It goes back to my childhood, because I had constantly to affirm my own self in an environment that reduced me to zero, an environment in which I had no standing, as it were. I was driven to find in the grounds of my being that which transcended everything in my environment (external to me). Once I hit it, then I knew I was home free, that the environment could never destroy me because at my center I would never say “yes” to the external judgment of me [as a Black man]” . . .

. . . Thurman often recounted a tale his grandmother (Nancy Ambrose) told to him and his two sisters. She would say, “Once or twice a year, the slave master would permit a slave preacher from a neighboring plantation to come over to preach to his slaves . . . But this preacher, when he had finished would pause, his eyes scrutinizing every face in the congregation, and then he would tell them, ‘You are not niggers! You are not slaves! You are God’s children!’ When my grandmother got to that part of her story, there would be a slight stiffening in her spine as we sucked in our breath. When she had finished, our spirits were restored.”

Luther Smith, Jr., in his wonderful book Howard Thurman: Mystic as Prophet, writes, “Nancy Ambrose was the first to teach Thurman that spirituality sustains one in the midst of life’s many predicaments . . . She witnessed to the power of her spirituality to meet one of the fundamental demands of life’s hierarchy of needs: the need to survive as a slave. This survival function of religion is not just addressing the condition of the body, but the survival of an identity—that center of a person which gives definition to one’s being.”

Thus, from an early age, Thurman learned from his grandmother’s and mother’s example, which included many religious practices such as prayer, Bible reading, church attendance, and spiritual conversations. Through their stories and modeling, young Howard became partially inoculated against the oppressive, racist messages surrounding him. Throughout his life he could survive and even thrive in an atmosphere that denied his humanity.

(excerpted from Lerita Coleman Brown, What Makes You Come Alive—A Spiritual Walk with Howard Thurman, 63-67. Used with permission).

***

What are the ways we shape our identity and sense of self by outside forces? How has our self-understanding been formed by the expectations of others?

How does contemplative practice offer a doorway into liberation from these external limitations and free you to become fully yourself? How might Love become your deep anchor and grounding in life and all that you do and say?

Join Lerita next Saturday as she explores the wisdom of Howard Thurman and his teachings on love.

With great and growing love,

Christine

Christine Valters Paintner, PhD, REACE

Dancing Monk Icon by Marcy Hall (prints available on Etsy)