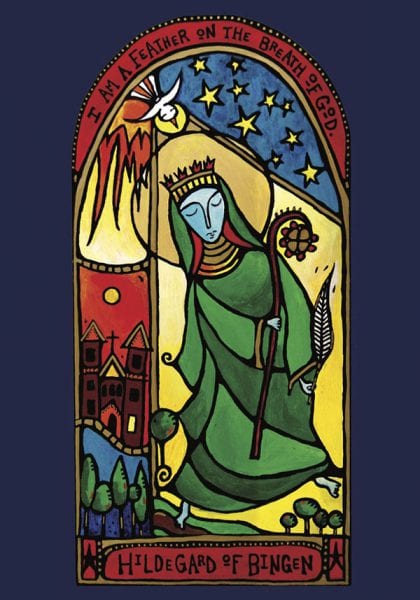

St. Hildegard Strolls through the Garden

St. Hildegard Strolls through the Garden

Luminous morning, Hildegard gazes at

the array of blooms, holding in her heart

the young boy with a mysterious rash, the woman

reaching menopause, the newly minted widower,

and the black Abbey cat with digestive issues who wandered

in one night and stayed. New complaints arrive each day.

She gathers bunches of dandelions, their yellow

profusion a welcome sight in the monastery garden,

red clover, nettle, fennel, sprigs of parsley to boil later in wine.

She glances to make sure none of her sisters are

peering around pillars, slips off her worn leather shoes

to relish the freshness between her toes,

face upturned to the rising sun, she sings lucida materia,

matrix of light, words to the Virgin, makes a mental

note to return to the scriptorium to write that image down.

When the church bells ring for Lauds, she hesitates just a

moment, knowing her morning praise has already begun,

wanting to linger in this space where the dew still clings.

At the end of her life, she met with a terrible obstinacy,

from the hierarchy came a ban on receiving

bread and wine and her cherished singing.

She now clips a single rose, medicine for a broken heart,

which she will sip slowly in tea, along with her favorite spelt

biscuits, and offer some to the widower

grieving for his own lost beloved,

they smile together softly at this act of holy communion

and the music rising among blades of grass.

— Christine Valters Paintner

Dearest monks, artists, and pilgrims,

September 17th is the Feast of Holy Hildegard, one of the patron saints of our work here in Abbey because of her roots as a Benedictine monk and Abbess, and her incredible commitment to creative expression and nurturing aliveness. I am currently in the Rhine valley in Germany co-guiding a group of pilgrims here to walk in her footsteps.

I am the living breath in a human being placed in a tabernacle of marrow, veins, bones, and flesh, giving it vitality and supporting its every movement.

—St. Hildegard of Bingen, Scivias I 4:4

Hildegard of Bingen was a 12th century Benedictine Abbess, who was also a theologian, visionary, musical composer, spiritual director, preacher, and healer. For centuries monasteries have been centers of healing and herbal medicine. Monks would grow the herbs and learn their applications, so that people would come for both spiritual and physical healing.

We have lost this connection, with medicine taking place in the efficient and sterile halls of hospitals. Please don’t misunderstand me, I am profoundly grateful for the gifts of modern medicine, and rely on it to some degree to maintain my own quality of life. And yet, we have lost so much in this shift from the model of slow medicine and healing to the pursuit of quick cures. In the process we have come to compartmentalize ourselves, seeking the fix for the headache or the stomach trouble, without considering the whole of our bodies and our lives. We become impatient when illness descends, rather than yielding to body’s needs and desires.

We rarely have a relationship with our doctors, spending only minutes with them each visit, whereas Hildegard, and other monastics like her, would have come to know her patients. She would have seen the profound connection between body and soul. She would have practiced slow medicine.

One of the fundamental principles of Hildegard’s worldview is viriditas, which means the “greening power of God.” But even more than that, it refers to a lushness and fecundity in the world, a greening life force we can witness in forests and gardens and farmland. Hildegard, who lived in the valley around the river Rhine in Germany, was profoundly impacted by her witness to the profusion of greenness and how this green life energy was a sign of abundance and life. It is what sustains and animates us.

Greenness became not just a physical reality, but a spiritual one as well. Hildegard believed that viriditas was something to be cultivated in both body and soul. Her language is filled with metaphors for seeking out the moistness and fruitfulness of the soul. The sign of our aliveness is this participation in the life force of the Creator. Anything that blocks this flow through us contributes both to physical disease as well as spiritual unrest.

For Hildegard, viriditas was always experienced in tension with ariditas, which is the opposite experience of dryness, barrenness, shriveling up. She would keep asking how to bring the flow of greening life energy back in fullness to a person.

Victoria Sweet, a medical doctor in San Francisco and researcher in medieval history, wrote a wonderful book called God’s Hotel: A Doctor, a Hospital, and a Pilgrimage to the Heart of Medicine in which she explored Hildegard’s principles of greening in her own medical practice. Dr. Sweet worked in a long-term care facility and began to ask the question of what was blocking a patient’s access to this life-giving greening energy and shifting her perspective enabled her to find healing paths that were previously unseen. She also discovered that simply being in relationship with her patients over time allowed her to see patterns and behaviors which revealed far more into their care than a quick visit could ever do.

There is a story from the desert fathers where an Abba says to a seeker, “Do not feed your heart what does not nourish it.” This can be easier said than done, since we are inclined to so many “comforts” which only serve to numb and distract us from life. How often do we try to satisfy ourselves with that which depletes us?

What if your fundamental commitment was to only offer your body and soul that which is nourishing and to listen to what depletes you and say no to those things.

I invite you to hold this question in all things: Does this nourish me or does this deplete me?

(We have a self-study online retreat to dive more deeply into the wisdom of Hildegard of Bingen and we hope to lead our next pilgrimage to Germany in 2021.)

With great and growing love,

Christine

Christine Valters Paintner, PhD, REACE

Dancing monk icon by Marcy Hall at Rabbit Room Arts