I am delighted to share another beautiful submission to the Monk in the World guest post series from the community. Our reflection this week comes from Kreg Yingst whose block prints of Mary are featured in Christine’s forthcoming book Birthing the Holy: Wisdom from Mary for Creativity and Renewal. Read on for Kreg’s reflection “The Creative Act as Spiritual Praxis*”

“Go, sit in your cell, and your cell will teach you everything.”

– Abba Moses

Some of the most magnificent works in art history have been the beautifully illuminated Psalters of the Middle Ages. These prayerbooks were for kings, queens, and only the very wealthy. When the printing press was invented in the fifteenth century, Bibles, religious books, and illustrations became affordable. Yet in all of my research I have yet to find one book of Psalms entirely illustrated with woodcuts. This surprises me somewhat since printmaking, especially in the fifteenth and sixteenth century, was often used for thematic cycles; most notably The Passion of Christ and The Dance of Death (Ars Moriendi; Art of Dying).

This void was the impetus for me illustrating the entire Psalter a number of years ago using relief prints. I had hoped to knock out the project in a relatively short amount of time, perhaps a year or so. These prayers, however, proved much more difficult than expected, predominantly because they weren’t narrative in nature which I was more accustomed to. What the Psalms did offer were poetic similes, metaphors and visual language that allowed me to transfer words into concrete images. Needless to say, the year came and went, then another, and then another. My discipline on the project waned, but not my desire.

For me, these scriptures, as difficult as they were to read and interpret became a devotional and my artwork became a prayer – or perhaps I should say the act of making art became prayer. The project took on a new dimension. There was a paradigm shift – one from rushing toward an end product to simply engaging with the Divine through the process. The journey became more important than the destination.

During the early Monastic movement, a time when few could read, monks would gather together around the abbot during the reading of the scriptures. There was an emphasis placed on memorization; not just engaging the word for knowledge, but for spiritual transformation as well. As a result, the monks would listen carefully and allow a passage of scripture to speak to them. St. Benedict incorporated this practice into his Rule for Monks, a prayer method which would come to be known as Lectio Divina or Divine Reading. The process required four stages: reading, meditating, praying and contemplating. My approach to the Psalms’ project would initially begin in this manner.

The scale I was working on was quite small however, and as I began to illustrate the Psalm in its entirety it became just too problematic. So I took a smaller bite. This would sometimes be just a sentence or two to use as inspiration for an image. A spiritual sound bite, so to speak, also had a name and was used by Christians well before St. Benedict’s time. It was known as Meleté.

In his book, Desert Banquet, author David Keller writes: “[Meleté] is the practice of repeating a verse or short phrase throughout the day…done silently or aloud at different times, [it] can help us remain centered on God’s presence in the midst of distractions and responsibilities that consume our attention. The ‘formula’ reminds us to always seek God’s help and reminds us that we are never without God’s presence. This simple practice destroys the myth that there is not enough time in the day for meditation. It enables us to pause several times each day to become mindful of what is most fundamental in life.”

There, in the silence of my studio, I was able to engage with the Creator through the act of creativity.

Perhaps the only thing during this project that had shifted for me from my usual practice of creating art was intentionality and awareness. The seventeenth century Carmelite monk Brother Lawrence speaks of a non-duality in the spiritual and practical life. “I rest with him,” he writes, “in the deep center of my soul…” There are spiritual practices we can come back to time and time again in living a holistic life, such as breath prayers, sacred reading, and fasting. These can be embedded into our daily activities in such a way as to create a continual awareness of God’s presence. Brother Lawrence affirms, “A little lifting up of the heart suffices. A little remembrance of God, one act of inward worship…” In the quiet of our cell, communion, rest, and creativity forms a sanctuary of the heart.

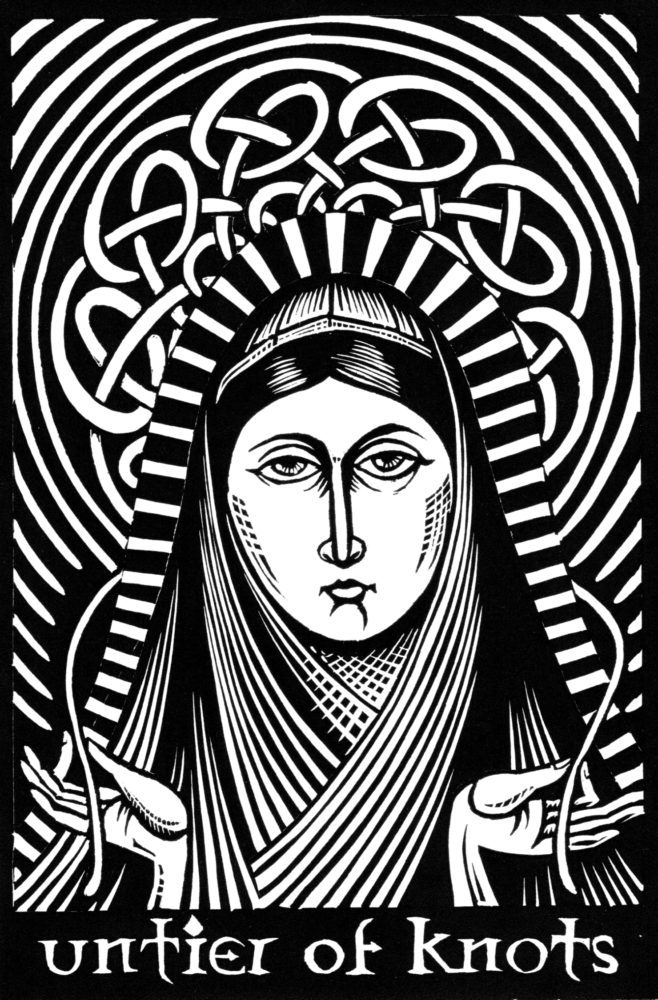

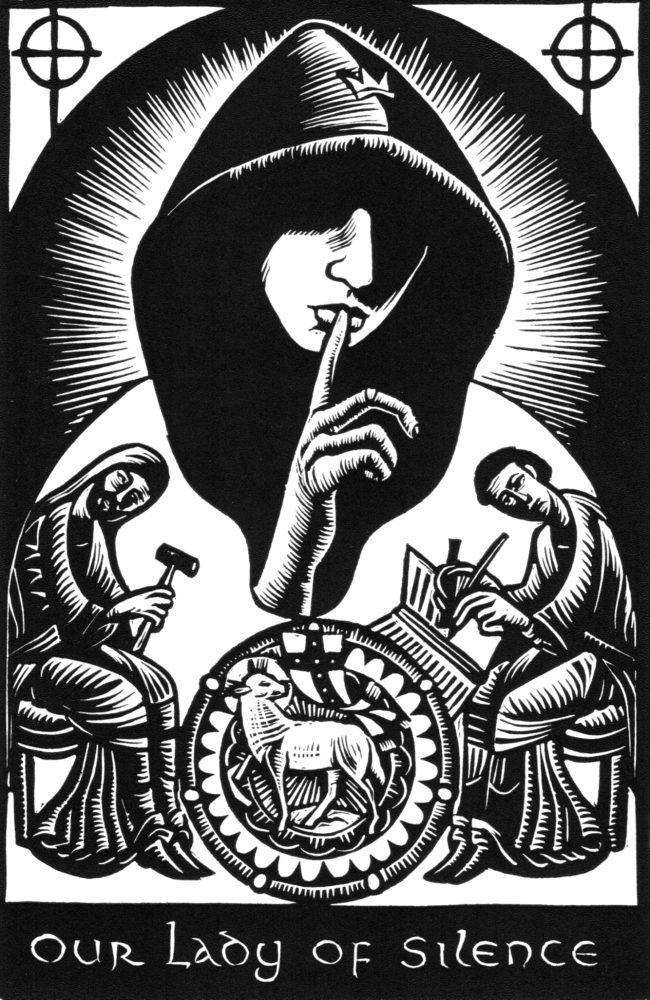

When I began work on the Marian series to illustrate Christine’s book, Birthing the Holy: Wisdom from Mary to Nurture Creativity and Renewal, my approach was very similar. I tried to use art-making once again as an act of contemplation. There was, however, one major difference from the previous project. Whereas the spiritual disciplines of Lectio Divina and Melete were initially used, both word based meditations, this time around Visio Divina and Art History would lay the foundation for centering. Rather than taking a word or phrase through the day, the meditational focal point became an icon or painting. The first step was to research the Marian title to be interpreted. And while reading was still essential in providing the needed information to proceed, emptying my mind during the actual art-making process became the gateway for images to emerge.

To create a conducive atmosphere in the studio, I rarely worked in silence. Too often during extended periods of quiet time my brain becomes filled with words, noise and distractions – what the Buddhists call “Monkey Mind.” This can, in fact, stifle the imagination. Abigail Fagan writes, “Even though the mind is a wonderful thing, it can sometimes get in the way of creativity, mainly because the voice in our head can get in the way of what our heart wants to say.” But if I’m able to fill that emptiness with the angelic harmonies of monastic chant, the pleasing melodies of Hildegard von Bingen, or the soothing instrumentals of the classical minimalists, these distractions float away into the ether.

As a novice in these ways of contemplation I’m determined to take the advice of Blaise Pascal that “in difficult times you should always carry something beautiful in your mind.” There’s a serenity in beholding through our inner vision the loving embrace of the Madonna and Child, and perhaps a unity with the world too when we view this love through the lens of different cultures. In a world of turbulence, distraction, and worry, of which we’re evermore experiencing these days, to be able to cultivate a mind of stillness and repose becomes an inner-source of healing.

*Praxis, the Greek word for “action that is habitually repeated,” is labor and vigilance directed toward inner spiritual formation, leading to love of God and neighbor. [David G. R. Keller]

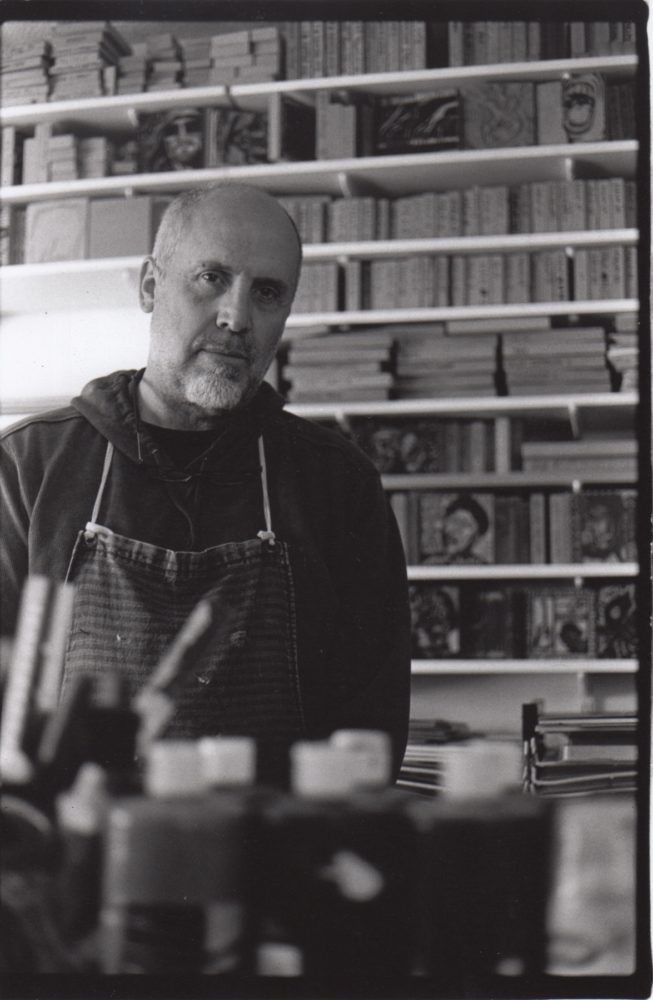

Kreg Yingst is a printmaker and painter living in Pensacola, Florida. His subject matter for the past twenty years has focused on people – Saints and sinners and everyone in between – while stories, poetry, lyrics and travel have always served as an unending source of inspiration. Yingst received his Bachelor’s Degree in studio art from Trinity University and a Master’s Degree in painting from Eastern Illinois University. His art can be found in private and public collections including Purdue University; The Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art at the College of Charleston, South Carolina; Janus Corporation, Denver, CO; College of Lake County, Grayslake, IL; and Pensacola State College in Florida. Visit his Etsy shop.