For the next few weeks I will be offering you some gems from the Abbey archives as I create the space I need to finish several writing projects and prepare for spring’s teaching.

Dearest monks, artists, and pilgrims,

The road of cleansing goes through that desert. It shall be named the way of holiness.

—Isaiah 35:8

If the desert is holy, it is because it is a forgotten place that allows us to remember the sacred. Perhaps that is why every pilgrimage to the desert is a pilgrimage to the self. There is no place to hide and so we are found.

—Terry Tempest Williams, Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place

In the fourth century, out in the desert landscape of Egypt, Syria, Palestine, and Arabia, a powerful movement was happening: the flowering of Christian monasticism in response to a call to leave behind the world. The center of this movement was in Egypt, and by the year 400 A.D. it was a land of hermits and monks experimenting with a variety of forms, including the solitary life of the hermit, the coenobitic or communal form of monasticism, and groups of ascetics.

The wisdom of this tradition forms the foundation for much of Christian spirituality that emerged in the following centuries, especially Benedictine and Celtic forms of monasticism. A literary genre emerged which was similar in form to parables and proverbs, story teachings to impart wisdom. These are gathered together in the Sayings of the Fathers (Apophthegmata Patrum), which include the wisdom of both the desert fathers and mothers.

The word for desert in Greek is eremos, which literally means “abandonment” and is the term from which we derive the word “hermit.” The desert was a place of coming face to face with death. Nothing grows in the desert. Your very existence is, therefore, threatened. In the desert, you can only face up to yourself and to your temptations in life, which distract you from a wide-hearted focus on the sacred presence in the world. The desert is a place of deep encounter, not of superficial escape.

We do not have to journey to the literal desert to encounter its power. Each of us has desert experiences, seasons that strip away all of our comforts and assurances and leave us to face ourselves directly. Each of us can benefit from the wisdom of the desert mothers and fathers who speak to us across time.

St. Benedict, who was deeply influenced by the desert elders, wisely wrote 1500 years ago, “Always we begin again.” As you move through your Lenten journey, you might want to write those words somewhere visible, to call you back each time your commitment to spiritual practice wavers. The desert is a place of new beginnings; it is where Jesus began his ministry. In the desert, we are confronted with ourselves, naked and without defenses, called again and again to bring back all of our broken and denied parts into wholeness.

The monastic cell is a central concept in the spirituality of the desert mothers and fathers. The outer cell is really a metaphor for the inner cell, a symbol of the deep soul work we are called to, to become fully awake. It is the place where we come into full presence with ourselves and all of our inner voices, emotions, and challenges and are called to not abandon ourselves in the process through distraction or numbing. It is also the place where we encounter God deep in our own hearts.

Abba Moses wrote, “A brother came to Scetis to visit Abba Moses and asked him for a word. The old man said to him: ‘Go sit in your cell, and your cell will teach you everything.'”

Abba Anthony wrote a similar message: “Just as fish die if they stay too long out of water, so the monks who loiter outside their cell or pass their time with men of the world lose the intensity of inner peace. So like a fish going toward the sea, we must hurry to reach our cell, for fear that if we delay outside we shall lose our interior watchfulness.”

Connected to the cell is the cultivation of patience. The Greek word is hupomone, which essentially means to stay with whatever is happening. This is similar to the central Benedictine concept of stability, which on one level calls monks to a lifetime commitment with a particular community. On a deeper level, the call is to not run away when things become challenging. Stability demands that we stay with difficult experiences and stay present to the discomfort they create in us.

In our cell, we are called to full presence to our inner life. We cultivate the inner witness and watch as our thoughts scurry between different states, notice our internal responses to things, and observe when our minds move to distraction as a way of avoiding engagement with life. The cell is the place where we grow in deep intimacy with our patterns and habits. When we become conscious of our methods of distraction, we can learn to bring ourselves always back to our experience.

For Lent, I invite you to cultivate presence to your own inner world. Allow yourself time for silence each day. In that space, let your breath carry you inward into your own monastic cell. Stay present with yourself as you notice emotions rising and falling.

Do you have an outer monastic cell—a room or space where you can pray without distraction?

How might you practice stability in your own life? What are the emotions that cause you to want to run in the other direction? Grief? Anger? Deep joy?

What are the ways you distract yourself from being fully present? We all have ways of numbing, whether through watching hours of television, surfing the internet, shopping, eating, drinking. Really, anything can serve as a way of numbing ourselves when we engage in them as a way of avoiding what we are experiencing within. Consider fasting from distraction this Lent and becoming more conscious of the ways you avoid staying with yourself.

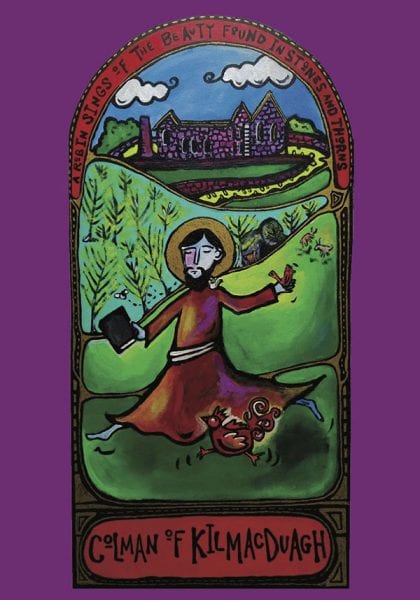

If an outer pilgrimage calls to you, our dates for 2016 in Ireland have now been posted and you can find more information here.

With great and growing love,

Christine

Photo by Christine: John Paintner on the trail up to Maumeen Pass where St. Patrick is said to have journeyed. This is one of the journeys we make with pilgrims in our new pilgrimages itinerary out of Galway.